A work by Wang Anbang (Drama, Nanjing University), Florian Geisseler (Film, Zurich University of the Arts), Mengying Li (Intermedia Art, China Academy of Art, Hangzhou), Joel Schoch (Composition for Film and Theatre, Zurich University of the Arts)

Concept

Cities are getting bigger, denser and tighter. In growing cities space gets limited and there is no more space for everyone. There are welcome and unwelcome persons and different strategies to prevent certain people from making themselves visible. The concept of our installation is an accumulation of objects, sounds and lights, that have only one purpose: To prevent certain people to be present, to keep persons out of sight and, hence, out of society. The installation collects these hidden strategies to an un-living and dead place to make aware of their presence.

Process

One day after Hong Kong was hit by the severe typhoon “Mangkut”, we set off with the camera for a first sightseeing tour. On the streets were severed branches, completely torn trees, loose paving stones and glittering glass splinters. There was a ghostly silence in the city, only a few cars making their way through the chaos. The huge windows of the blocks of flats sticking out into the sky seemed dead and inanimate.

Under one of the many highway bridges, we came upon a stone structure that in its regularity reminded of a sea or the plowed soil of an arable field. The stones embedded in the ground were so sharp that it was impossible to walk over them. But in this undoubtedly very aesthetic structure lies an inhumane intention. To prevent homeless people from settling under the bridge. Later on our reconnaissance tour we passed countless other blind spots under bridges, stairs and underpasses, which were made impassable with different consequences.

From this impression, the starting point for our first project has developed for us. The structural aesthetics and serene beauty of this intrinsically brutal intention, and the peaceful aesthetics surrounding this place at the same time stayed with us. In the stone structure we saw a strong symbol for the displacement of a certain marginal group from the public space and at the same time the structure attests to the absence as well as the existence of this fringe group.

This has resulted in various questions which we wanted to investigate in an initial research phase. On the one hand, we wanted to find out who the homeless people are and where they live. On the other hand, we wanted to deal with the public space in Hong Kong. Who owns the public space? Why is there a separate rule board on each bridge, in each underpass, and how do you have to behave?

As a result, we learned about homelessness in Hong Kong and tried to find out where the displaced people live. Quickly we came across an underpass near the Causeway Bay Station. The people we met in this tunnel were well furnished. Partly between the mattresses and protective tarpaulins were wooden cabinets, chairs and chests of drawers or electronic devices such as televisions or fans. Many of the people were elderly. After asking, we learned that the people in the Causeway Bay tunnel are not able anymore to pay the rising rents, and that they can no longer afford a flat, although many still work every day.

As we have further discovered, the public space of the city is privatised. The land is leased and if you use part of it as a public footpath, you can build higher. For this reason, there are very different regulations in public space and therefore also different measures for the abortion of marginal groups.

After these new insights, we have again thought about the subject of the project. For us all, the topic of homelessness seemed very complex and Hong Kong-specific. Since the exhibition would be in Shanghai, our intention was to create a work that could also work outside of this particular city. Because we wanted to work with the means of photography in an installation framework, we also had ethical concerns. How far can we approach this topic without just exposing the suffering? Are we then not contributing to making people even more marginal? In addition, we had doubts about our ability to do justice to the complexity of the topic within the mere four weeks that we had left until the vernissage. That’s why we decided to focus on the means of repression. Through our installation, we wanted the visitors of the exhibition to feel the inhumanity of this associative architecture.

As a result, we looked for other types of displacement methods that we also know from Switzerland. Quickly we came to the blue neon light that has been seen since the drug hell of Platzspitz in the 90s in every public restroom, every blind spot and in every underpass of the city of Zurich to prevent the heroin users of seeing their veins. In addition to intentionally short kept benches, preventive armrests, concrete grooves and stone beds, we also had to think of the high frequency beeping, which is only audible to young people. In all these means, we saw unspoken guidelines on how people should behave in public space, where they can stay, where not and above all, who.

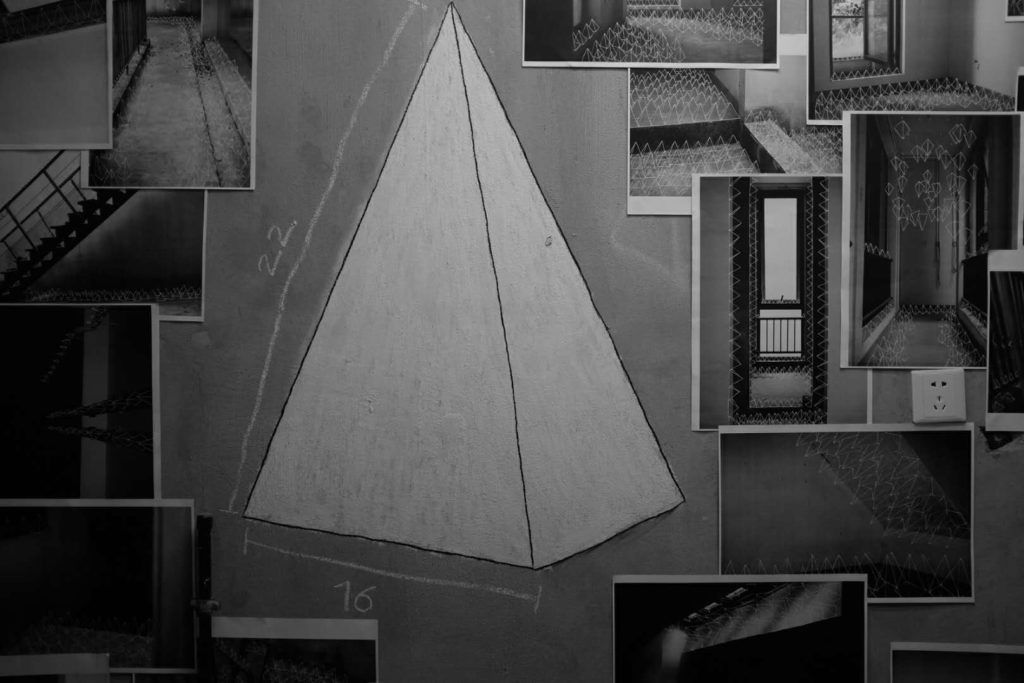

From these thoughts we formed our first concept. In a small, dark room of the empty villa, we wanted to build a structure out of gypsum pyramids, which fills the entire space and makes it impregnable. The ceiling we wanted to equip with blue neon lights and from time to time a high whistle should surprise the visitors. At the end of the room, three small photographs of public places from Hong Kong were supposed to hang, so that the public would like to take a closer look at them, but would be hindered by the pyramids. The room was to become a single dead and inanimate place.

However, in the discussions about the subject, we soon became aware that we are creating an unclear narrative with far too many different elements. While the combination of the different and very specific symbols may be a good aesthetic experience, it may still be too inaccurate in its thematic focus. Do we want to do a work on the homeless people of Hong Kong? About the question for whom the public space should be there? Lack of space in a steadily growing city? About city politics and the unscrupulous real estate market? Or even about the drug scene in Zurich? A reason for this arbitrariness we saw in our reality-oriented narration. We decided to limit ourselves further and give the installation a fictitious framework.

Result

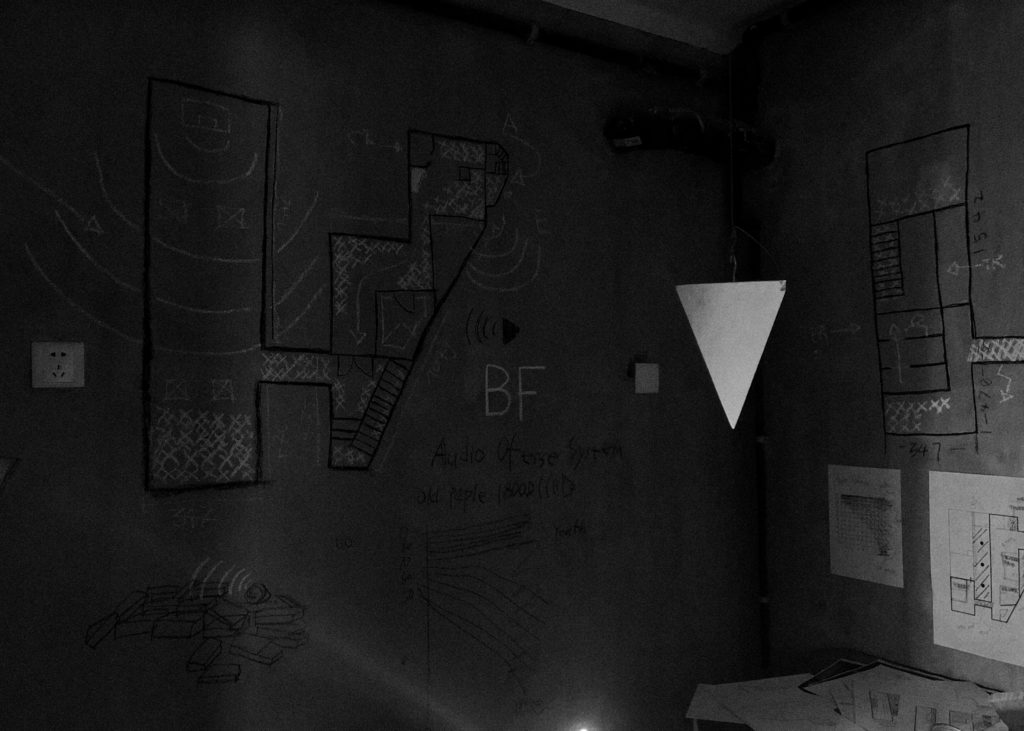

In the final work, again we tried to address the audience directly and to use the whole architecture of the abandoned villa. For this purpose, we created a character who wants to defend his living space from the visitors of the art exhibition opening. The character should not be present in person, the installation should only give a glimpse of being closed to the outside world. Thus, we designed a room in the basement as his small experimental laboratory, where he forges his defence plans in a gloomy atmosphere. On a metal table with office lamp, we have prepared various plans, sketches and photos of the villa with notes that illustrate where and how best tips and audio defences can be set against the art public. The walls of the room were smeared with wild carbon drawings of the plan and sketches of the pyramids. In a second room, we have built a dense structure of the pyramids, which spreads to the next room and there passes in chalk drawings on the ground. From a sound system the thoughts of the character could be heard in the form of an audio diary. Throughout the villa, we placed dense chalk drawings of the gypsum tops on the floor.

The final work was thus a reflection on the exclusion and the simultaneous foreclosure. The installation uses the means of associative architecture and is directed directly against the art-interested public. Therefore it could be read in its fictionalisation as humorous anti-art, but also as a reflection on real-life events on a personal, social and political level.

- {“ARInfo”:{“IsUseAR”:false},”Version”:”1.0.0″,”MakeupInfo”:{“IsUseMakeup”:false},”FaceliftInfo”:{“IsChangeFacelift”:false,”IsChangeThinFace”:true,”IsChangeEyeLift”:true,”IsChangeNose”:false,”IsChangeMouth”:false,”IsChangeFaceChin”:false},”BeautyInfo”:{“SwitchMedicatedAcne”:false,”IsAIBeauty”:false,”IsBrightEyes”:false,”IsSharpen”:false,”IsOldBeauty”:false,”IsReduceBlackEyes”:false},”HandlerInfo”:{“AppName”:2},”FilterInfo”:{“IsUseFilter”:false}}

- {“ARInfo”:{“IsUseAR”:false},”Version”:”1.0.0″,”MakeupInfo”:{“IsUseMakeup”:false},”FaceliftInfo”:{“IsChangeFacelift”:false,”IsChangeThinFace”:true,”IsChangeEyeLift”:true,”IsChangeNose”:false,”IsChangeMouth”:false,”IsChangeFaceChin”:false},”BeautyInfo”:{“SwitchMedicatedAcne”:false,”IsAIBeauty”:false,”IsBrightEyes”:false,”IsSharpen”:false,”IsOldBeauty”:false,”IsReduceBlackEyes”:false},”HandlerInfo”:{“AppName”:2},”FilterInfo”:{“IsUseFilter”:false}}

- {“ARInfo”:{“IsUseAR”:false},”Version”:”1.0.0″,”MakeupInfo”:{“IsUseMakeup”:false},”FaceliftInfo”:{“IsChangeFacelift”:false,”IsChangeThinFace”:true,”IsChangeEyeLift”:true,”IsChangeNose”:false,”IsChangeMouth”:false,”IsChangeFaceChin”:false},”BeautyInfo”:{“SwitchMedicatedAcne”:false,”IsAIBeauty”:false,”IsBrightEyes”:false,”IsSharpen”:false,”IsOldBeauty”:false,”IsReduceBlackEyes”:false},”HandlerInfo”:{“AppName”:2},”FilterInfo”:{“IsUseFilter”:false}}