Text written by Samuel Toro Perez, Tian Jun Wong, Fang Yun Yang

1. The question

In the very beginning of our working process we tried to formulate a basic question. While the common desire for a performative format and the emphasis on body movement became obvious quite soon, the matter of content seemed to be rather a challenge. After some days of discussions, brainstorming and parties, we found a topic which would guide us through our creative process without narrowing us down too much – inspired by observations and details of daily life in Hong Kong from our different perspectives:

How environment, people and objects influence and form each other.

Also some pragmatic considerations were important for planning our project, such as the fact that we were going to have two performances, each of them concluding a time frame of three weeks for exploring, tryouts and rehearsing, as well as a break of one week between these two phases. A second important fact consisted of the performance locations, the XXX gallery in Tai Kok Tsui and the Academy of Visual Arts of the Hong Kong Baptist University in Kai Tak. Throughout the whole process we were working in several constellations, sometimes including just two of the three group members. Not only did this flexibility allow us to shift from idea to idea in a spontaneous and playful way and to work also while not all of us were free, but the fact that one of us would sometimes jump in again after a short period of absence would always cause moments of surprise and more objective feedback, which again could provoke spontaneous inspiration.

2. Rethink

The first tryout session took place in Victoria Park, featuring Tian Jun and Fang Yun, focusing on the physical impact of objects on people. We chose Victoria Park as our first experimental field since it provides different kinds of facilities for physical exercise and leisure time.

- Snapshots and corresponding sketches from the tryout at Victoria Park, exploring ways of interaction between dance and drawing.

While Fang Yun was moving on specific facilities, trying to find ways of fitting her body in, Tian Jun attempted to capture both the objects and the respective dance movements by line drawing into her sketchbook. The fact that the dancer would constantly move, confronted her with the challenge of drawing constantly and quickly, always shifting her view from Fang Yun to the paper and vice versa. Experiencing and reflecting these moments of synchronous movement between drawing and dancing led us towards another important aspect of our project:

Deconstruct and rethink our disciplines.

We were fascinated how naturally a supposedly nontimebound art form like drawing (and painting, later on) could turn into a notably performative and transitory form of expression.Rethinking the drawing from this perspective, it became an act of recording and transcribing the very present of body movement at each moment rather than a snapshot of an object or a person per se. We went on applying this idea throughout the whole collaboration process.

3. The present

It became clear to us that we needed to leave behind the traditional relationship and hierarchy of working process and result in order to create something live instead of showing something created in the past. We liked the idea of the drawer not only presenting her finished artwork or creating it in front of the audience but as a performer who would be as much a subject to change at any time as her drawing and who could act and react as well as observe, capture and document.

Alternative emphasis.

Basically, we first experienced how deconstruction and decomposition could generate not only the possibility but the necessity of a new way of regarding our art practice’s potential within this context. We started to focus on aspects which normally tend to be considered as merely functional or as side products, sometimes even as unwanted or at least lacking of any aesthetic quality by themselves, take place off stage etc., such as the actual movements executed in order to play a scale on the guitar or the sounds which are created by dance, the act of practicing and rehearsing or the question of stage presence.

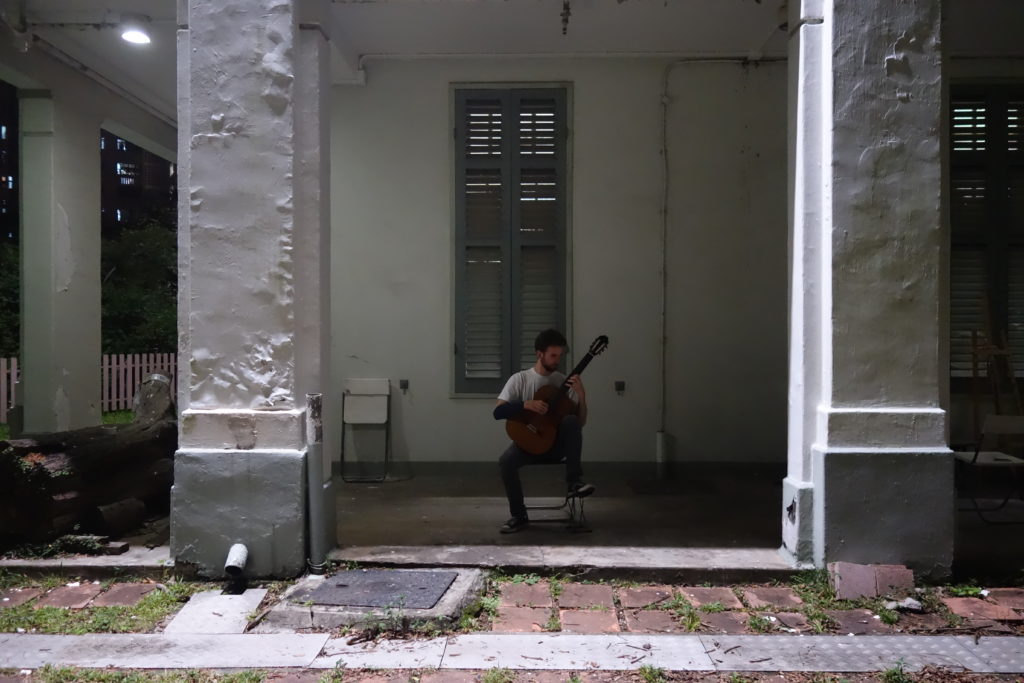

- Shooting the video about stage presence (left side) which we projected as part of the performance (right side). Coming from behind the column on the left side, Samuel would go on stage, sit down and take his performing position and posture without actually starting to play; then he would go off stage, walking towards and disappearing behind the column on the right side. We looped it and experimented with different speed levels, also during the post production.

The research process during the next four weeks could be described as a battlefield of three different art forms. We tried to improvise with each other as a way to unfold every discipline and decode its respective language, playing with ambiguity, interpretation and different meanings as well. The three disciplines were taking messages from each other and getting transformed within their own language at the same time, creating another art form together. During the first week we experimented with a setting where Tian Jun was leading, painting on canvas. The dancer would follow the music played by the guitarist, while continuously adapting his way of playing according to the pace and quality of each of the painter’s strokes.

Snapshot from our improvisation session at Connecting space.

Tian Jun was trying different brushes, fabrics, paper and types of pigments (including ink) in order to create distinguishable textures and strokes during these improvising sessions. Finally, she narrowed down the pigments to ink in order to simplify the concept (and, besides that, it turned out to be an important input for defining our project’s title).

4. Sitespecific

Meanwhile, we got inspired by Craig Edward Dykers, a designer of architecture who raised the question “What happens when a situation is not constructed? What can challenge people to create alternative understandings of a place? What can make people forget or remember? In fact, in this project we really took the space as an input, adapting and 1 further developing the ideas from our previous tryouts.

To give an example, the beginning of the final performance included a dancing section all over a corridor. The dancer literally included the space into her choreography interacting with the objects in the space by performing different kinds of movements. She would use repetition as a way to discover the space and communicate with them. You could say that in a certain way the objects and the space itself were forming the dance piece and its choreography by shaping the body movements. We consider this as a precise artistic example of environment shaping our quality of movement. As a complement of the dance part, the painter was simultaneously creating sounds with two contact microphones at the other end of the corridor using them like brushes, creating a transsensorial illusion of painting the sound. The idea was to question and play with causality between movement and sound, still presenting it in an authentic way.

- Alternative emphasis on dance and painting: Creating live sounds for the dancing part performing painting movements during the Corridor sequence.

At the same time, Fang Yun was leading the audience from the starting point towards the other side of the building where the major part of our final performance would take place. They hadn’t been told about it before, but as the dancing part was leading more and more towards the other end of the corridor, they naturally followed the implied invitation to discover the space themselves – as well as the actual author and source of the sounds. At any time of the whole performance, the audience could always choose their perspective and decide to change it. We were actively playing with the audience’s expectations, sometimes breaking them and thereby emphasizing the present as well as by offering them different levels of activity.

The audience was following the performers along the venue.

5. Connecting

Basically, while gathering more and more inspiration material by decomposing our disciplines along with discovering lots of new possible settings and playing with their different aspects, we had smoothly taken the next step:

(Re)create connections between them.

We were conscious about those traditional and sometimes even stereotypical forms of connection, such as choreographing a piece of music or composing music based on a painting. Neither did we really stick to them nor did we try to ignore or neglect them. Instead, we took them as an inspiration for further development and tryouts, such as inverting them, transferring them to another constellation and omitting some of its essential parts. During another of our sessions in pairs, which took place at the Connecting space Hong Kong, Fang Yun and Samuel were exploring and experimenting with different aspects of body movement as part of their usual way of performing.

As a first input they chose a sequence of the solo guitar piece “Un sueño en la floresta” by Agustín Barrios Mangoré. While Samuel performed it several times, Fang Yun reacted to it following different criteria: She would dance reacting “movement to movement”, focusing on one body part of the guitarist and moving herself just a specific part of her body, thus generating a bodytobody translation of a sequence of movements which usually would be considered as mainly functional for achieving a piece of music as a result. The parameters for this translation turned out to be quite different depending on the body part chosen as the source and its corresponding movement quality. The decision that the dancer would follow the guitarist’s left hand and arm basically dancing with her torso and shoulders strongly implicated a direct adaptation of the obvious horizontal movements in the first place, whereas following his right hand, whose movements were smaller and harder to distinguish, needed to be done in more abstract way. Notably this path of abstraction brought up some creative confusion and started to unfold a vast field of possibilities of conception and perception.

As a next step we repeated these experiments – physically excluding the guitar from the guitar performance, narrowing down the source to the part we were actually interested in, simplifying the setting and at the same time excluding the result of the guitar performance’s movements and thus its original aim. Without any sounding music and just the imagination of the instrument to be played, the level of abstraction was higher for both performers and the setting itself became less predefined, i. e. more open, although the performed movements were still corresponding precisely to the act of playing the original guitar piece. We also included the “air guitar performance” in our final performance.

Tryout session focusing on possible relationships between dance and music performance (top). Air guitar performance as part of the final show (bottom)

Now Samuel could stand up and walk during the experiments as well as his counterpart. We had already planned to play with shadow as well, so at some point we decided to add a spotlight to the setting, which proved to be very fruitful. Now that our focus had shifted towards the shadow, our movements became bigger and more holistic.

Then we took the guitar back in and thus included sound in the shadow experiments, aiming to loosen the relationship between sound and movement: The source would still be a composed piece of music for guitar requiring a certain sequence of movements, but we wanted to try to find a way of shaping them by the pace and quality of dance (including the possibility of thus distorting the original music), which turned out to be interesting, challenging and contradictory at the same time.

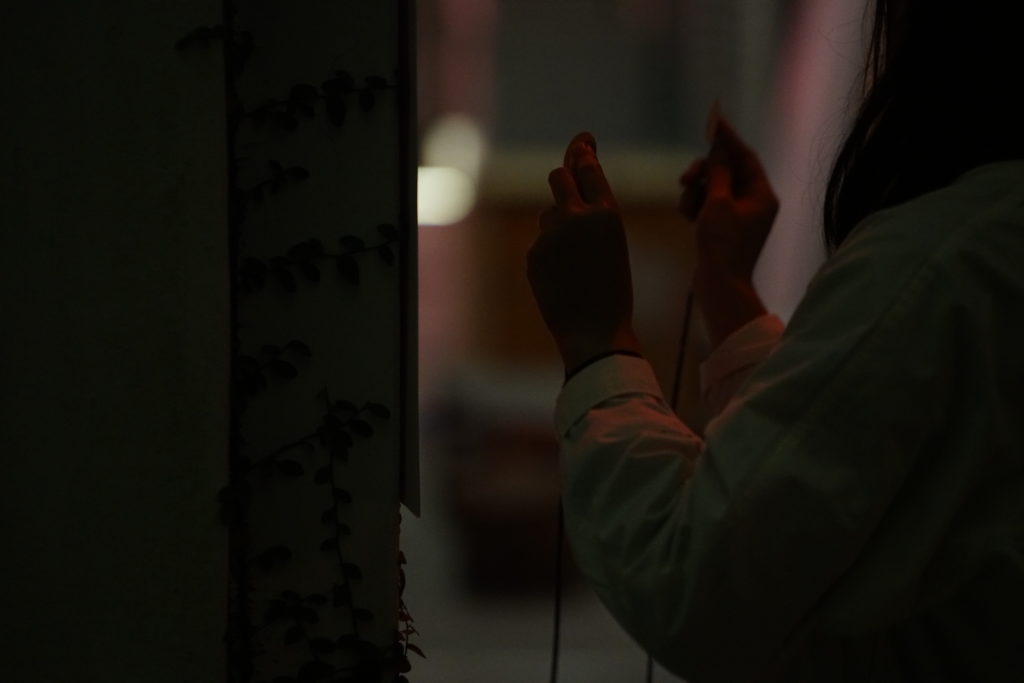

Inverted causality: The dancer leading the guitar player during his performance

Finally we completely switched the causality between guitar and dance performance, retaking the idea of direct translation, firstly based on improvised dance. Samuel automatically aimed for a translation with a musical priority but then slowly shifted towards a more movement focused way of guitar improvisation. In order to make it more easy and also clear, Fang Yun again narrowed down the movement source to her arms and choreographed a short phrase which she would repeatedly perform. This last rather simple setting turned out to be pretty productive and easy to develop further.

After the first experiments with “air guitar performance” and “contact microphone painting”, we got interested in applying the idea of removing the discipline’s original medium to dance as well, or in other words, how would you appreciate a dance piece without actually seeing the body movement of the dancer?

We were approaching this question while developing the middle part of the final performance, featuring live painting with ink on a big white screen located at the building’s facade of the second floor instead.

The setup had been visible already during great parts of the piece, without giving any hint about what would happen there or when. Tian Jun was standing behind the screen at first, the audience would just see her shadow due to the blue coloured light spots located behind her. Thus, when she started to paint, her actions were visible both as the movement of her shadow and as the result of her brush strokes painting black ink on the white fabric.

Full view of the performance venue at the Academy of Visual Arts, from the audience’s perspective after the initial Corridor sequence.

It was our clear intention to let the audience focus on the strokes, which were a live translation of Fang Yun’s second performance of the initial Corridor choreography taking place on the same balcony as painting screen, starting from the opposite corner and moving towards it. We created an additional visualisation of the strokes’ movement by attaching a GoPro camera onto the wrist of Tian Jun’s right hand, which was holding the brush, projecting the movement from the perspective of her brush as a live video feed on the other big screen at the first floor. Due to technical reasons, there would always be a certain delay between the real brush stroke and its corresponding video projection which blurred the connection a bit. On the other hand, this facilitated the audience to observe the same stroke both ways, one after another (if starting with the painting itself).

- Details from the second part of the performance. Fang Yun dancing on the second floor (left) and Tian Jun painting with the GoPro camera attached to her wrist (right).

Adding another layer of translation, Samuel was improvising on the guitar in direct reaction to the GoPro stream, located invisibly behind the projection screen. In the beginning, the music was of rather noisy character, again literally translating movement into movement. After some time, the connection between the strokes’ movement and the music would gradually loosen, with the music opening up the scope of different sounds and becoming more and more independent, finally creating a transition towards the next major sequence of the performance.

Through the synchronization of music, body movement and painting, the image contained the pace while recording and displaying the dance piece. Thus the image became a score combining music and dance, while the painter created a body movement by its own at the same time, shifting the attention from the final image to the painting process and its conditions.

Finally, we we decided to cancel the dancing part, limiting the number of visual sources to two for the sake clarity . Consequently, we came back to the question of how to make the audience still perceive the choreography as the very source of all the sequence or, in other words, of how to refer to it by indirect and implicit ways of expression. At the same time we aimed to generate a certain arc of suspense including a growing expectation and desire for the collective presence of all the three disciplines together on stage.

6. Completing the circle – harmony and disruption

Besides this kind of implicit tension, we were looking for situations of explicit suspense and disruption. Especially Dimitri de Perrot, one of our mentors, encouraged us not only to look for synchronicity and harmony orientated ways of connecting our disciplines but to go for moments of confrontation and conflict as well. He insisted that including the possibility of disrupting as well as creating – including things which had just been created – would provide us with more possibilities in terms of creativity and authenticity.

Following his advice, we had some sessions the three of us together where we tried to create as well as disrupt, distort and destroy. During the first three weeks we were working with very simple setups from which we defined the following elements for the first performance at the XXX gallery: long rolls of paper (which were suspended from the ceiling), ink as for the painting part, Samuel’s guitar, a chair and a footstool and two blue/purple spotlights.

During our experiments we came to the conclusion that two main resources for disruption and distortion were the paper sheets and ourselves. We discovered ways of interacting, guiding, stopping and interrupting each other, at different pace and quality and both with different intentions and effects.

Perhaps the most continuous element of disruption all over the whole project began to unfold when we started to experiment with composed guitar music from the Classical repertoire during our tryout sessions. Beside dancing and painting together with Samuel’s guitar performance, we started to discover different possibilities and levels of limiting his range of movement, irritating or interrupting him and included this matter in our script.

In the beginning of our first performance he was hidden, silently sitting on a chair with his guitar in playing position, surrounded by four paper rolls which were suspended from the sides of the air conditioning unit on the ceiling (thus being in permanent and slightly irregular movement under the ventilation and producing corresponding noise). During the first minutes he would just improvise based on what he could hear from the other two performers, very quietly and rather using noises than pitches or melodious sounds. Following a cue of Fang Yun’s, he would start to play an excerpt of Joaquín Rodrigo’s solo guitar piece “Invocación y danza” (based on Manuel de Falla’s ballet “El amor brujo”).

- Snapshots from beginning of our first performance at the XXX gallery: Beginning (left) and disruption (right).

This in turn would provoke Tian Jun to approach his paper cage, discovering him with her brush through the paper and leaving traces of ink, first gently, then gradually more and more vividly, at some point beating the paper in the dance rhythm of the music and, at its climax, resolutely tearing it down and wrapping it around Samuel’s head, completely interrupting his playing and blindfolding him.

We kept working with “Invocación y danza” until the final performance and adapted the moment of tearing the paper to the new setting (replacing the paper with fabric), expanding it by cutting with a knife and continuously tearing little by little during the “cooling down” phase after the musical climax towards the end of both the music and the performance, concluding by the final signature with our group name.

The final sequence: Samuel was performing “Invocación y danza” by Joaquín Rodrigo on the guitar, sitting behind the screen which now worked as canvas and shadow projection surface at the same time. Fang Yun was dancing behind him with an LED lamp in her hand, creating a shadow synthesis of Samuel’s and her own movement. Tian Jun was painting this shadow on the front side of the screen, following both its movement and the music’s arc of suspense, also cutting and tearing it at a certain point and finally signing it as a painting of the present moment.