We spoke with historian Monique Ligtenberg about how Switzerland was involved in the colonial period in Indonesia, what the repercussions are to this day, and what it all has to do with the documenta scandal.

To understand Indonesia’s history better, what colonial period are you referring to in your research?

In my own research, I focus on the late 19th and early 20th century. I am particularly intrigued by this era as it was coined by very intensive and violent warfar, conducted by the Europeans in Indonesia. Secondly, I find this period very interesting, because the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869 significantly shortened the travel routes between Europe and Asia. As a consequence, immigration from Europe to colonial Indonesia increased, which led to a number of new tensions. One of these tensions arose from the increased presence of European women in Indonesia, who were thought to be in need of protection from the threats of indigenous men, who were believed to be „irrational“ and „oversexualized. This in turn led to an increased racialization of society. The Dutch installed three legal categories aliged with the presumed civilizational development of the „races“: European, Indonesian and so called foreign Orientals, which included the Arabic and Chinese populations.

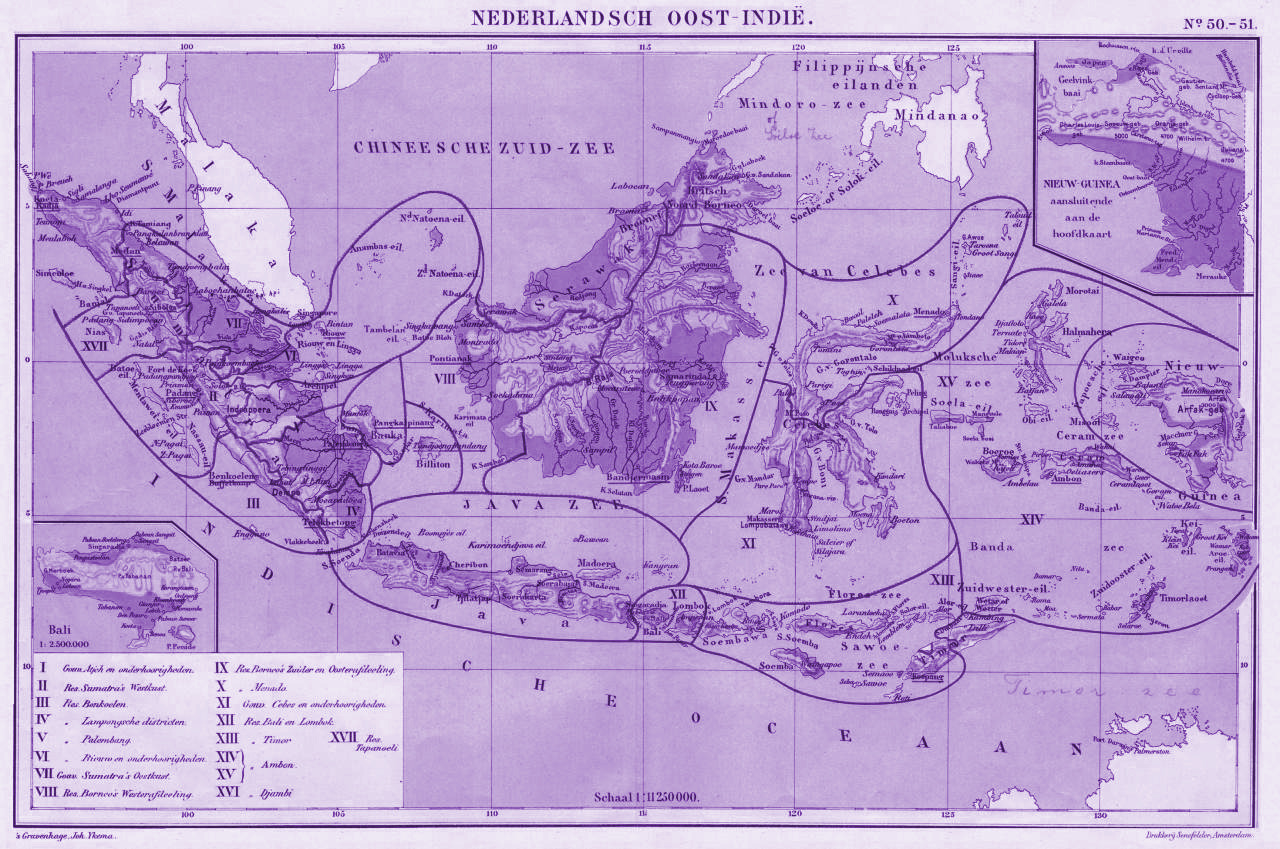

The third reason for my interest in this period is that I’m a historian of science. The late 19th century brought with it a couple of interesting developments in science as well, for example, through the discovery of the bacteria. The European obsession with pathogenic micro-organisms was a very colonial story, because tropical diseases such as malaria, threatened the settlement and military conquest of colonies such as Indonesia. Another interesting development at the time was the institutionalization of „race science“, that legitimized European rule over non-European populations. Many scientific discoveries were thus inextricably linked to colonial power exercise. But these are just my personal interests, the history of colonialism in Indonesia is of course much broader. It goes back to the 17th century, with the foundation of the Dutch East Indies trading company (VOC), which also already heavily impacted the demographic, social and economic structure of today’s Indonesia through violent conquest, through the monopolization of spices and related interventions in the local agriculture and environment.

In your project you focus on medicine, masculinities and colonial knowledge. I’m curious, in which way does masculinity played a part in those physicians, who entered the Dutch indies?

The question of masculinity is one I came up with originally because of the historical sources on colonized Indonesia. Something that always struck me is that most of the written documents of from the colonial period are authored by European men. We thus have very few documents that are written by women or by Indonesians themselves – especially, but not exclusively, in the history of science, in itself a very male-dominated sphere. This is a massive issue in imperial history more broadly, as colonial power always entailed granting or denying people the right to speak. What initially triggered me to think about the role of masculinity in colonial science or in colonial power exercise was not taking for granted that a majority of sources reflect the perspectives of European men, but rather to ask myself, what we can learn from the fact that European men were the people who had the right to speak and what that says about the ideological character of a very white, male community of scientists and politicians, bureaucrats, planters and slave traders. By showing that the striving of men to become powerful in itself was an ideology, I hope to destabilize the claim that colonial rule was something natural, or something that was predestined to happen.

What parallels or connections do you see between the history of Indonesia and Switzerland?

The connections can be traced back to the era of the Dutch East Indies trading company. The VOC was one of the biggest companies of its time with dozens of ships and the Netherlands were a very small country with a very small population. So what this meant is that they were dependent on workforce from other European countries. Switzerland’s predecessor, the „Alte Eidgenossenschaft“, was one of the regions where the VOC would recruit soldiers or sailors, physicians, cooks or craftsmen, to work on their ships.

On the one hand, they enabled the VOC to trade goods or spices from Indonesia, and on the other hand, to conduct warfare against people who resisted its empire building. One example for this is be the genocide of Banda from 1609 to 1621, where the VOC murdered thousands of Bandanese people in order to solidify its trade monopoly on nutmeg. It is highly likely that Swiss mercenaries were also involved. The recruitment of Swiss mercenaries continued in the 19th and early 20th century. In the 19th century Indonesia became a proper colony in the sense that the Dutch state started ruling over the territory, whereas the VOC was private trade company.

The Dutch states, eastablisehd a colonial army, which again, had to recruit people from all around Europe.

Calculations by the historian Philipp Krauer show that around 8000 Swiss men served the Dutch colonial army from 1814 to 1914.

Some of them who survived and returned to Switzerland actually lived pretty good lives.

One example would be Louis Wyrsch, who was an officer in the Dutch colonial army in the early 19th century and aided the Dutch in the conquest of Banjarmasin on today’s Kalimantan. After returnign to Switzerland from his service, he became a very important politician in the canton of Nidwalden. This political career was only possible because of the money and pensions he received from the colonial army, because at the time being a politician was not a paid job. He was also involved in drafting the first constitution of the Swiss Federal nation state. And his son, whose mother was Wyrsch’s indigenous housekeepter in Borneo, would become a member of parliament. Today we assume he was the first Swiss Member of Parliament of color.

Furthermore, many Swiss scientists travelled to Indonesia, in collaboration with the Dutch colonial government. They would loot thousands of cultural objects, zoological and botanical specimens, many of which they brought back to Switzerland and that are actually still in Swiss museums today. It is likely to assume that some of these looted objects, include human remains, skulls and bones, which were used for so -called anthropometric measurements at the time, that laid ground for race science. One of the long term consequences of colonialism is thus that a great part of the cultural heritage of Indonesia is located today in European, including Swiss, museums.

A third dimension in which Switzerland was involved in colonized Indoneisa is the economic one. Towards the end of the 19th century, for example, around 60 Swiss men would travel to Sumatra, to establish tobacco plantations, after the Dutch liberalized their markets. These plantation systems were highly exploitative. They included something we call indentured labor, which is often compared to slavery. The employees on these plantations would suffer severe violence, and they basically had no rights. They could just be shot on the spot, without any consequences for their European murdereres. They had to work very long days, and could not move around freely. And here again, we have an interesting example, which can be felt today. The Swiss Karl Fürchtegott Grob was among these planters. He employed around four thousand indentured laborers, became very rich and came back to Switzerland, as one of the wealthiest Swiss people of his time. He built a very decadent Villa in Zurich, the Villa Patumbah, which is heavily inspired by his exoticised fantasies of Indonesia. It’s really a very weird building, it looks like it was built by a boy, who had a dream of Asia. So there’s again, a lot of masculinity at play there. It’s an urge to show to the world what you’ve seen and actually inscribe that into your own home.

Let’s talk about the work „People’s Justice“ by the Indonesian art collective Taring Padi that was shown at the documenta and caused a scandal. How do you connect the images or graphics shown with the history of Indonesia?

One first thing that’s important to mention with respect to Taring Padi is that this art collective was founded in 1998 in the context of severe protests against Suharto, who was the second president of Indonesia and basically a military dictator. He came to power in 1965/66, being the master mind behind the genocide committed towards alleged communists and people of Chinese descent in Indonesia. In the course of this genocide, between half a million and three million people were brutally murdered by the Indonesian military led by General Suharto, who would then gain power and serve as Indonesia’s president for about 30 years. During his rule, there was very little freedom of speech and political opposition was violently supressed. Under Suharto, there were major human rights violations committed. People who protested his regime were frequently killed, tortured and abducted. Besides ethnic minorities, who wanted to become independent because they didn’t feel like they belonged to Indonesia’s Muslim Javanese majority culture, were violently oppressed. Timor Leste, for example, was occupied by the Indonesian military from 1975 to 1999, whereas tens of thousands of people lost their lives.

Now what does this has to do with a lot of the imagery on the Taring Padi banner? First of all, we can see that the banner caricatures military officers, which is a reference to the military dictatorship. Another thing we can recognize on the banner is that it includes a lot of anti- capitalist and specifically anti-Western or anti-American imagery. This has to do with the fact that the Suharto dictatorship was closely linked to the Cold War. In the logic of the Cold War, the US and other Western countries were very eager, in the logic of the so called domino theory, to constrain the influence of communism globally. The genocide in 65/66 was, as recent research has shown, heavily supported both financially and materially by the US, by Great Britain, probably also by Germany. The influence of other Western countries still has to be researched fruther. What we can say is that the entire western block, turned a blind eye on the 65/66 killings. There have so far been no convictions, no reparations, at no public apologies for the victims of the genocide and their descendants.

The Taring Padi banner also includes one figure which wears a helmet that says Mossad on it. This is one of the figures that was framed as being particularly anti-Semitic. With regard to this figure, I would differentiate a bit more. For one, because I believe it to be a reference to the Cold War era, and Israel was among the states supporting Suharto’s rule. Mossad, the Israeli Secret Service was probably involved in some ways in supporting Suharto’s anti-communist purges. The second aspect that was criticized about this image was that this Mossad soldier is depicted with a pig’s face. I don’t know the intention of the artists, but I would again argue for a more nuanced interpretation.

As we know, Indonesia has a Muslim majority, meaning the pig is haram. It is frequently used by Indonesian art collectives to insult some kind of enemy. It’s also often appears as a symbol for capitalism in the artwork of Taring Padi. So that might be an alternative interpretation.

When we talk about the second figure, which received a lot of media attention, namely the depiction of an Orthodox Jew wearing a helmet with SS symbols on it, I would say this is clearly anti-Semitic imagery. There’s absolutely no way to differentiate this even further. As a historian, however, my first question here would be to ask myself how it found its way onto this banner and to tie it to historical context.

If we talk about anti-Semitism in Indonesia, we again have to talk about colonialism. Anti-Semitism wasn’t something that existed in Indonesia prior to the arrival of the Europeans, because there was literally no Jewish community in Indonesia. This changed with the arrival of the Europeans in the 19 centuries, who imported increasingly negative connotations of the Jewish religion as well as anti-Semitic stereotypes that were prevalent in Europe at the time. Something that we can read very frequently in colonial sources is, for example, an equation of the Chinese minorities in Indonesia with the European Jews. Europeans basically said, the Chinese are the Jews of Asia. And they meant this in a very negative way, kind of transposing the stereotypes of „the Jews“ on them.

A second influence was the increased racialization of society towards the end of the 19th century that was also felt within the Indonesian population. This led to an increasing hierarchical sense of ethnic or cultural differences and superiority, with the Javanese majority being privileged over other communities.

In the 1930s, many Europeans in Indonesia actually supported the NSDAP (National Socialist German Workers’ Party), or its equivalent in the Netherlands. Again, anti-Semitic ideology was thereby disseminated through Europeans.

A furhter important aspect to mention when it comes to anti-Semitism in Indonesia would be cultures of remembrance or history education under the dictatorship.

So let’s jump back to the Suharto dictatorship, which, as I said, was very restrictive. This could also be felt in school education. The former colonization of Indonesia significantly damaged the national confidence. One of the major roles of historical remembrance was thus creating unity and national consciousness through school education. If you look at Indonesian school textbooks from the time, they mostly focus on Pahlawan Nasional (national heroes), which is still the case today.

It gets even more interesting when we look at what is not discussed in history education, especially under Suharto who was very eager to present a positive image of the West. First of all, that meant that the impact of colonialism was heavily played down. Second, World War Two was not really seen as a negative event, because it marked the independence of Indonesia that became independent in 1945.

World War Two was an event that marked the transition from a colonial state to an independent country. This means, in turn, that the history of the Holocaust or the Nazi regime were not in the center of what was considered to be important.

So what does that mean in relation to the banner? Indonesia definitely has to catch up when it comes to problematizing anti-Semitism in it’s society, remembering the Holocaust and educating people about the Nazi regime. But on the other hand, I think there is a qualitative difference, if somebody in Germany drew this image, coming from a country in which people are fully educated about the Holocaust, and nevertheless chooses to use this imagery. Or if we talk about a member of an Indonesian art collective, somebody coming from different cultural background, somebody who grew up in a dictatorship with restricted access to information and with state propaganda being implemented in school education, including history education, and then draws this image.

I’m not saying this as an excuse, we have to condemn this kind of imagery anywhere at any time. I’m saying in order to fight anti-Semitism globally, we have to take into account the cultural specificities and the historical genesis of anti-Semitisms around the world in order to enter into a dialogue. I think big parts of the German public and media have not been willing to actually understand where the Taring Padi imagery came from. That was a big mistake, because it’s not only a sign of Western arrogance and ignorance, but it’s also unproductive in this shared goal of eradicating anti-Semitism globally. If there’s no attempt to understand where a certain ideology comes from, there will be no dialogue and nothing will change.